Venue: Belvoir St Theatre (Surry Hills NSW), Feb 21 – Mar 22, 2026

Playwright: Sam Holcroft

Director: Margaret Thanos

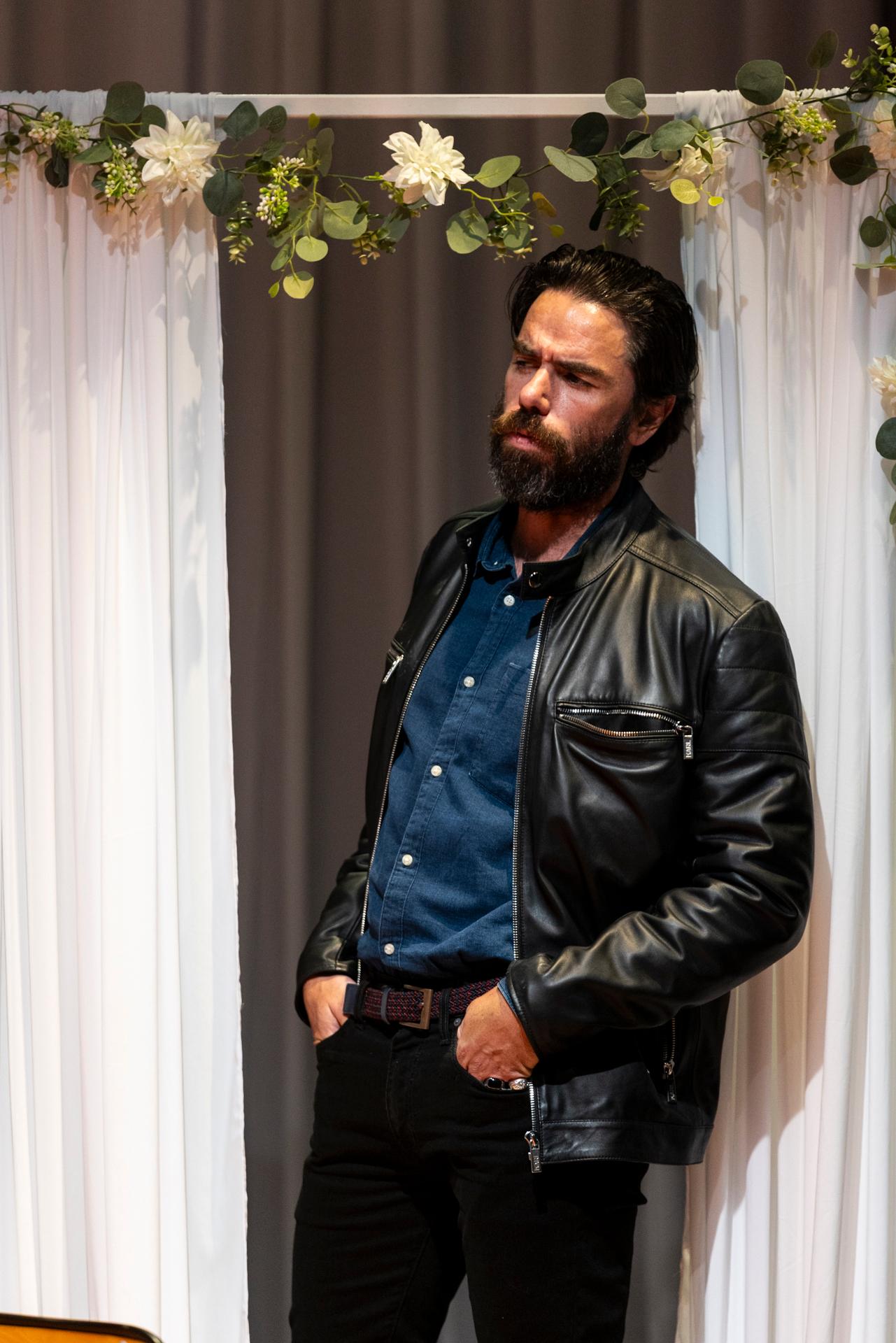

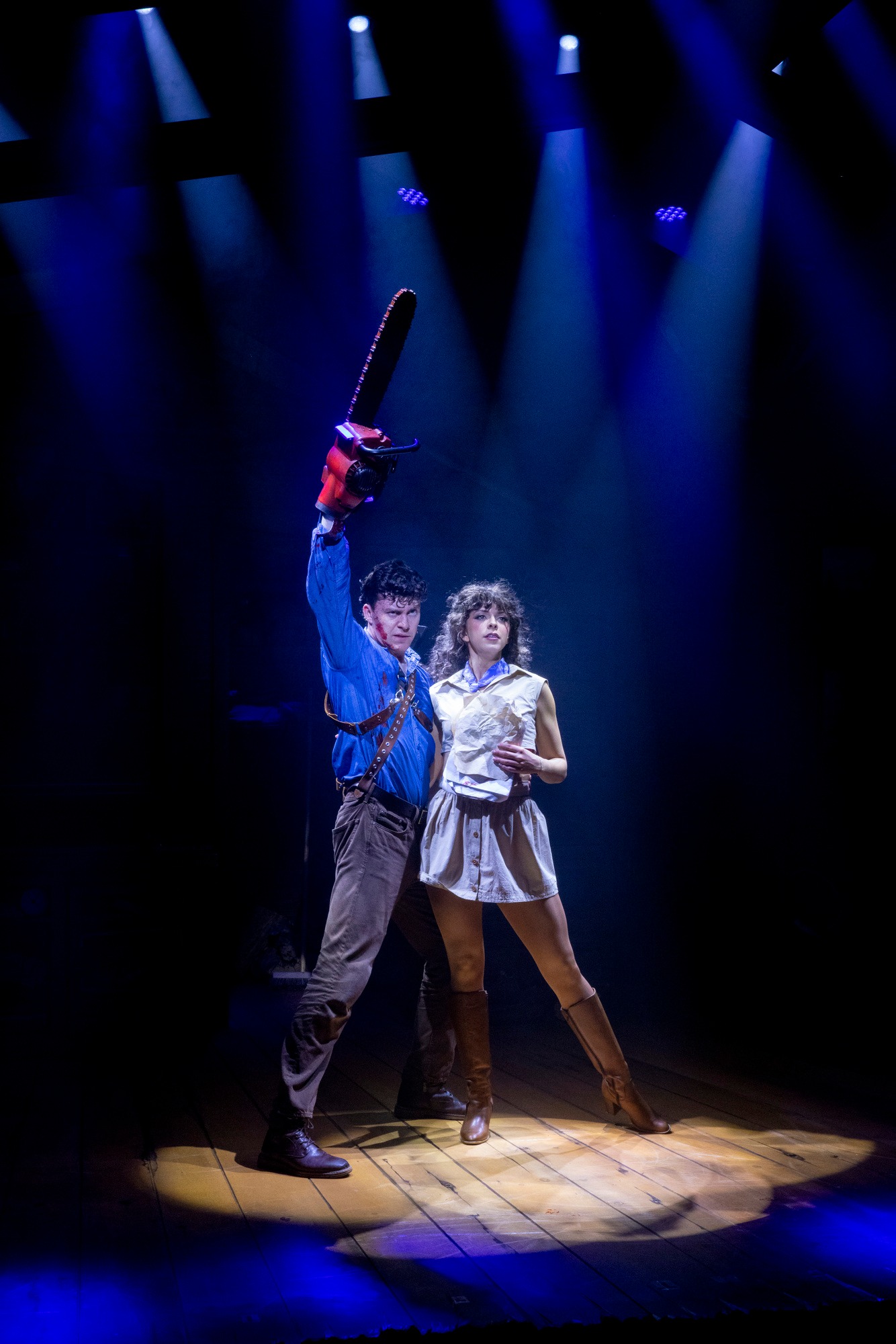

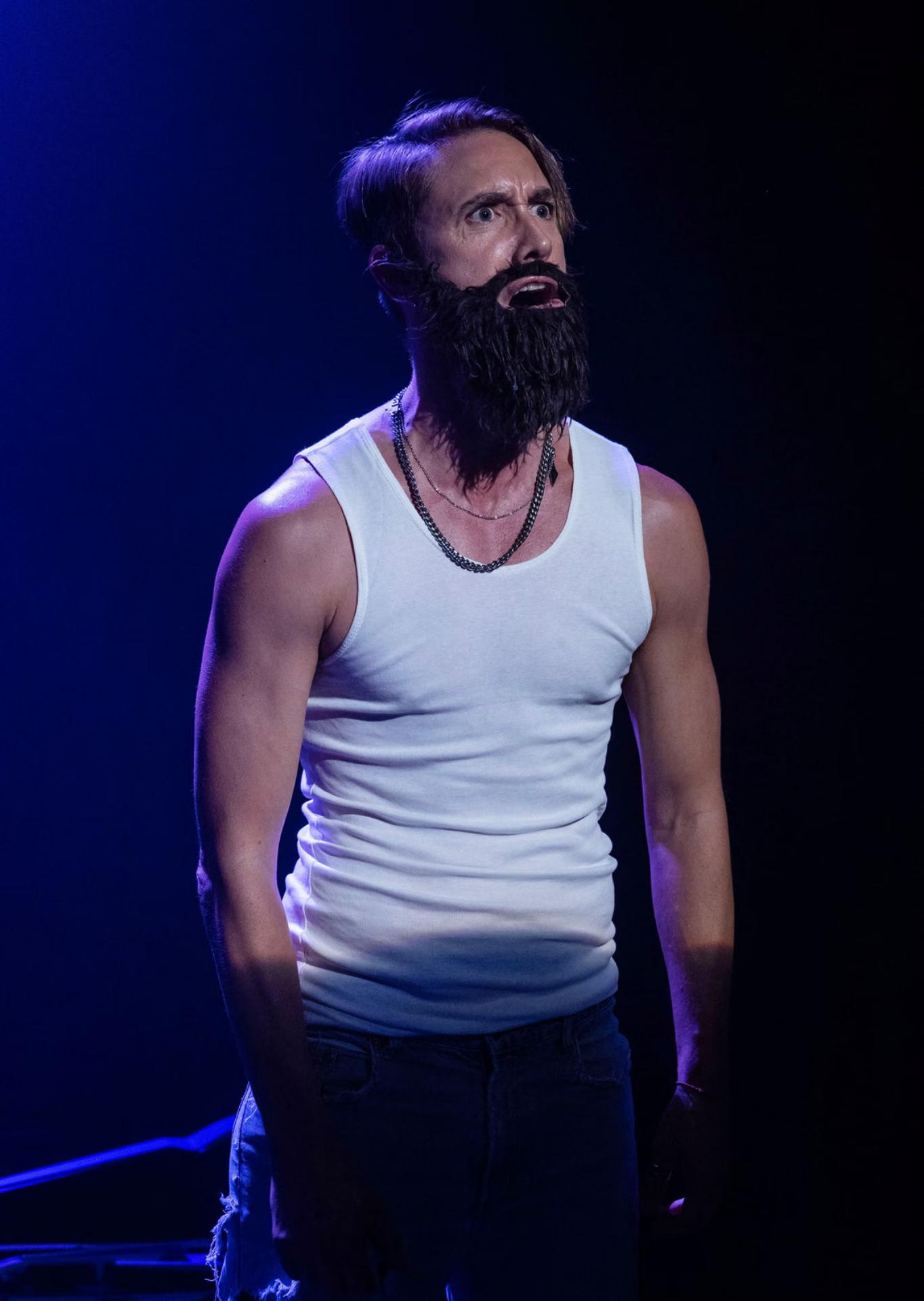

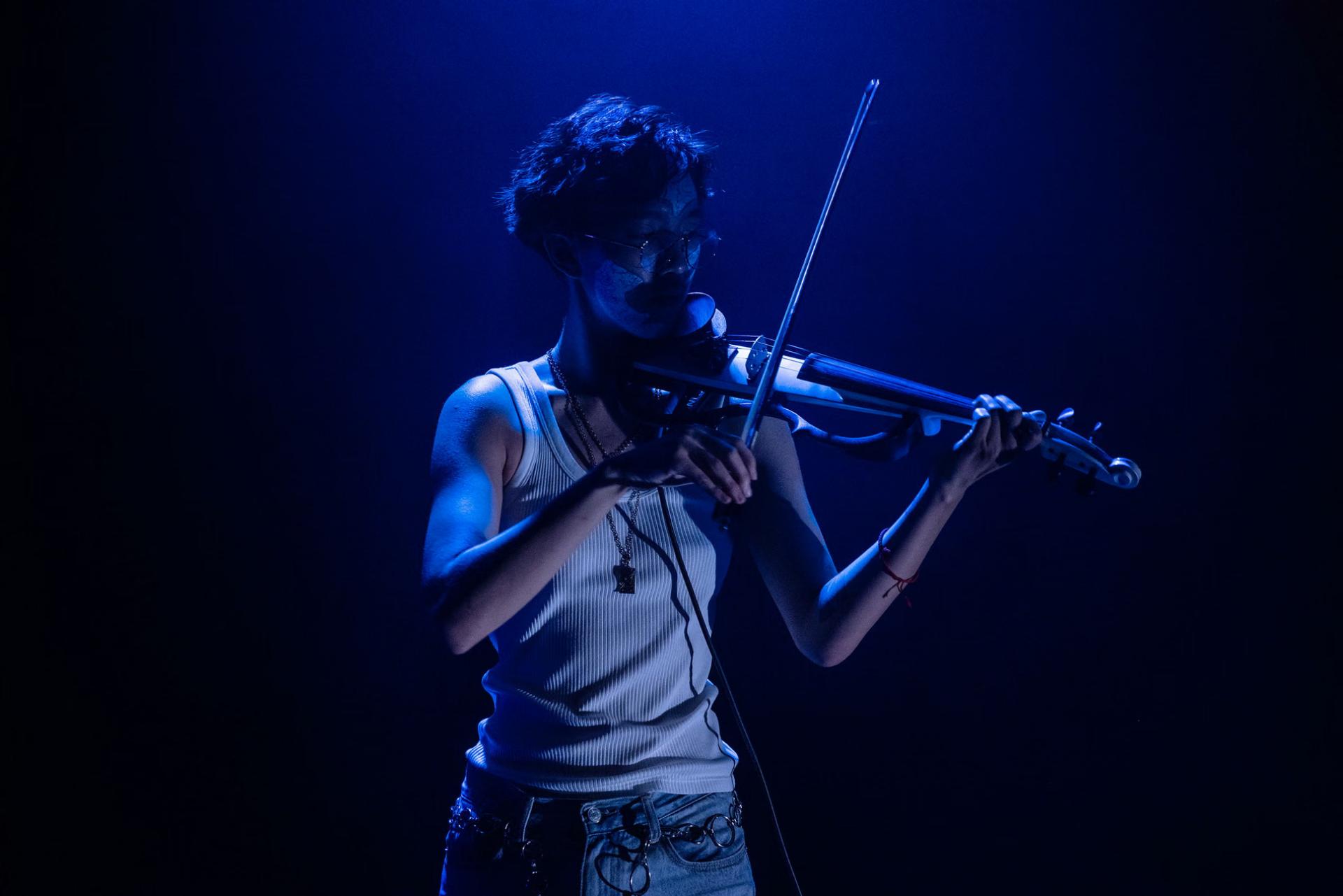

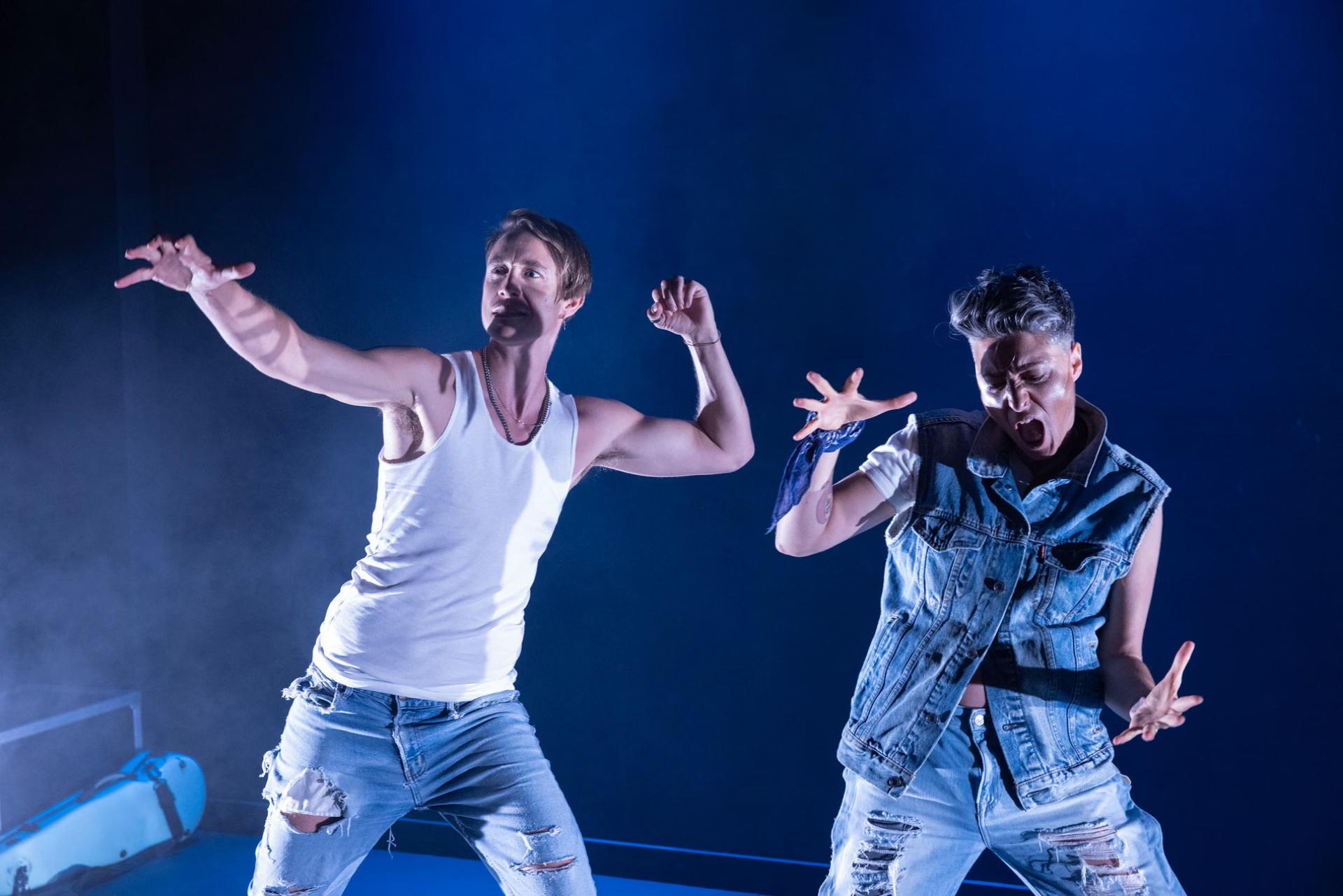

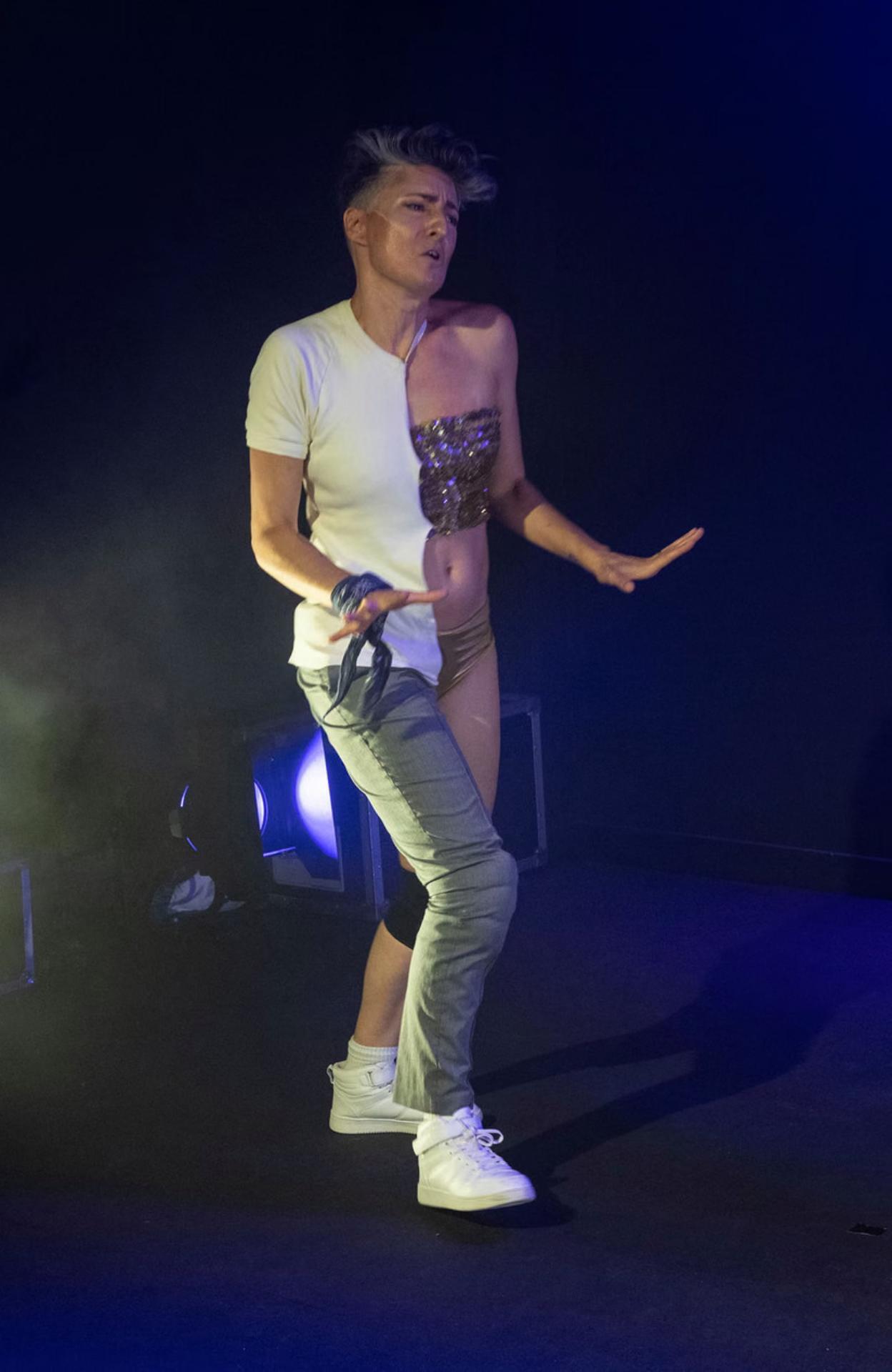

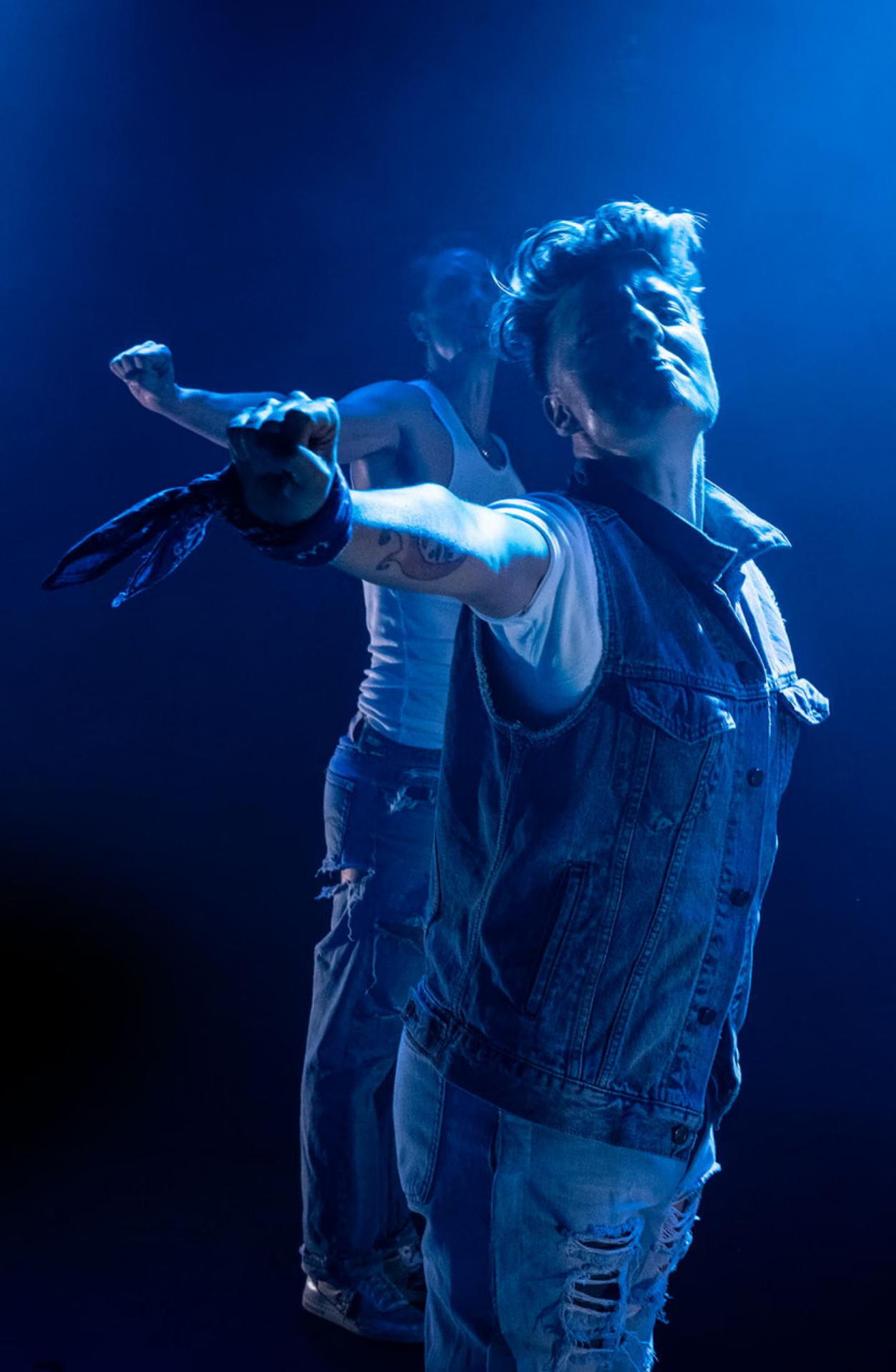

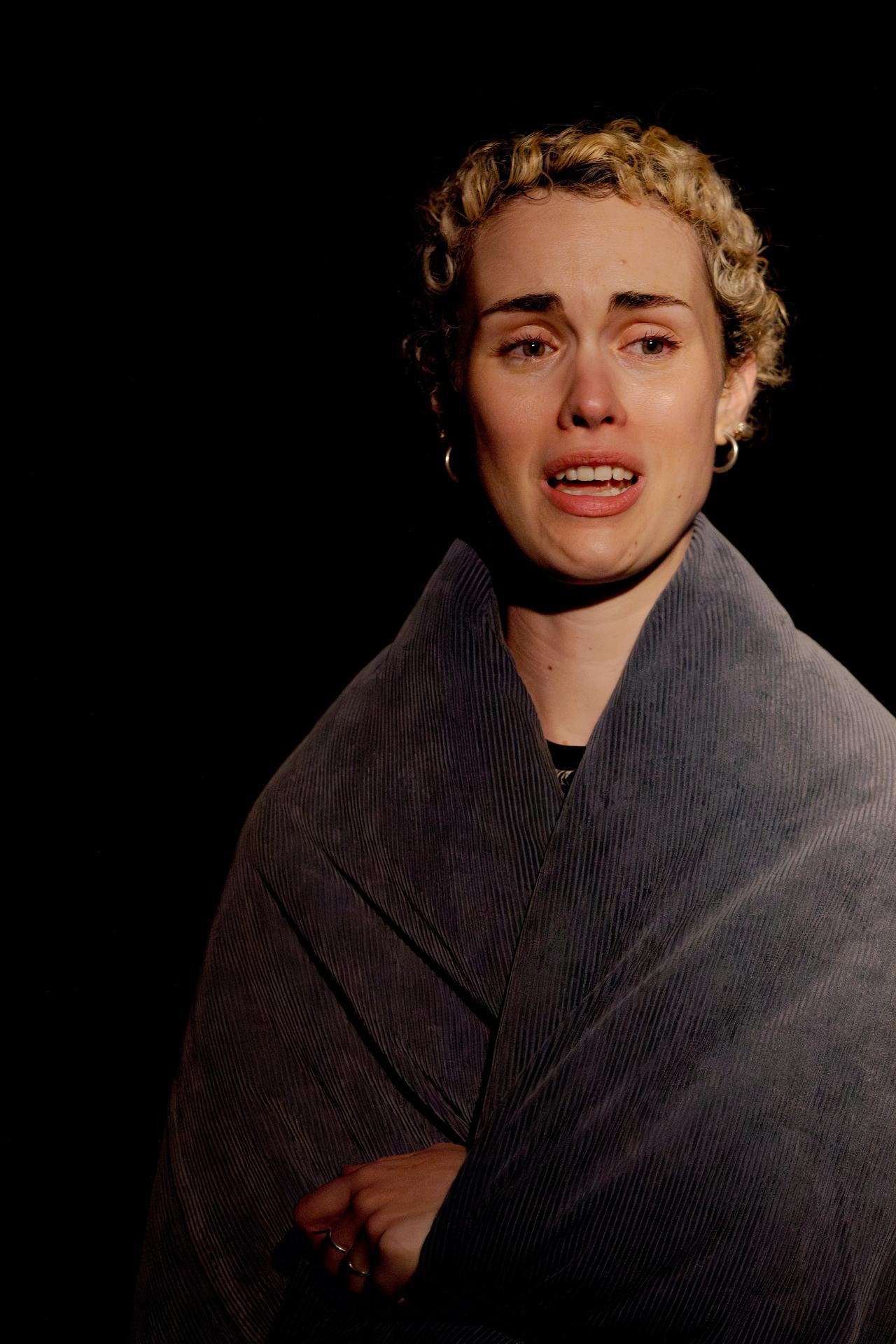

Cast: Eden Falk, Faisal Hamza, Yalin Ozucelik, Rose Riley

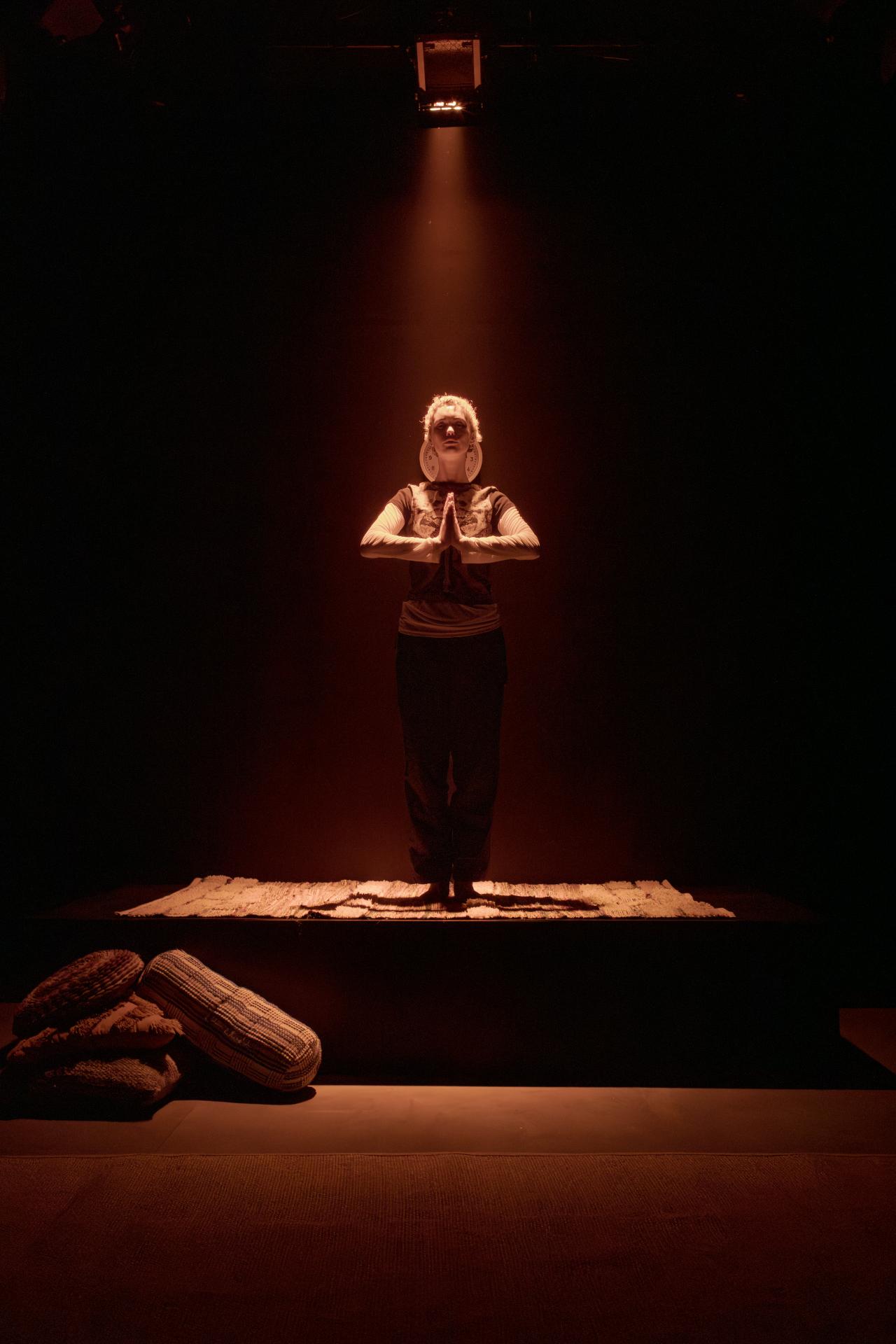

Images by Brett Boardman

Theatre review

A clandestine troupe stages a subversive theatrical production, its barbs aimed squarely at the Ministry of Culture and its censorious apparatus. Interwoven throughout are meditations on the nature of representation itself—whether literal or fictitious—as though artists must cleave to one pole or the other. Sam Holcroft’s A Mirror opens and closes with considerable force, yet the intervening dramaturgy wanders in states of descriptive and ideological confusion.

The decision by director Margaret Thanos to render an authoritarian regime through Australian voices, produces an effect of unintended absurdity, particularly when measured against the evident depth of our own democratic institutions (in comparison with other nations). There is, undeniably, a kernel of truth in the play’s suggestion that socioeconomic forces shape the conditions under which art is made, but whether Holcroft’s heightened, schematic approach can resonate meaningfully beyond that observation is less certain. What lingers is not the intricacy of the political critique, but the more elemental, perhaps eternal, truth that enduring work has always demanded of its makers one indispensable quality: courage.

The principal quartet—Eden Falk, Faisal Hamza, Yalin Ozucelik, and Rose Riley—bring considerable acuity to their respective roles, yet seldom cohere into an ensemble that transcends the sum of its parts. For all the mounting urgency of their narrative arc, little of enduring resonance remains once the final curtain falls. The design elements, too, settle for competence rather than distinction. Angelina Daniel’s set and costumes, while serviceable, lapse into staidness precisely where theatrical boldness is most required. Phoebe Pilcher’s lighting and Daniel Herten’s score prove their mettle in moments of heightened tension, yet falter during the protracted stretches of naturalism, which grow unnecessarily dour.

It is undeniable that fascism is ascendant across the globe. In Australia, democratic institutions appear, for the present, intact—yet the historical record offers scant comfort. Subversion, after all, requires no novelty of method; the same infiltrations attempted for centuries persist, adapted to contemporary conditions. Authoritarian regimes, almost without exception, train their sights first on the arts and the media—not merely as instruments of propaganda, but as sites of potential resistance. History demonstrates that while the wholesale destruction of a creative culture may require extreme force, the systematic erosion of democratic voice is altogether more achievable, more insidious.

The possibility that such a future could take root here is not abstract; it is a latent condition, ever-present. What stands against it is not inevitability, but resolve. The more tenaciously we hold to our convictions—the more defiantly we insist upon critical thought, and the messy, generative space of artistic freedom—the less hospitable this society becomes to the despots who would claim it. Resistance, in this sense, is not a dramatic gesture, but a sustained practice.